Bratrstvo

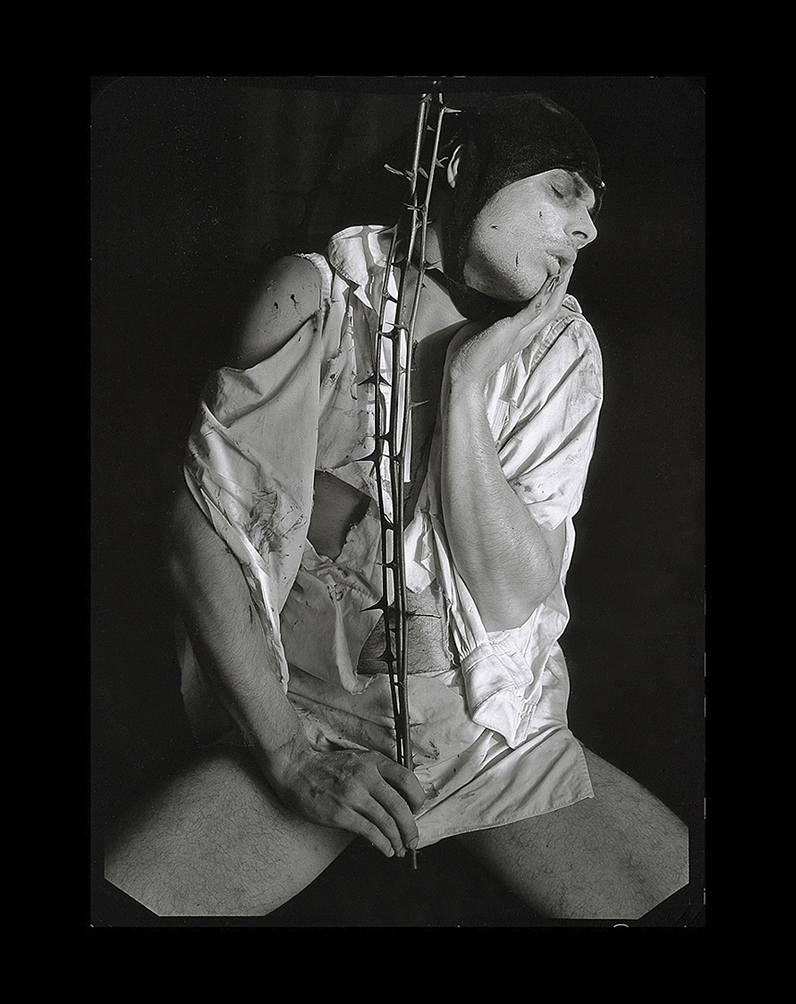

The Bratrstvo’s photographic output recycles intense attributes from various visual forms, encompassing both fine and applied arts—folk ceremonies, old art and Catholicism, totalitarian ideologies, or the iconography of capitalist advertising in fashion or music—without regard for their original purposes or clear new aims.

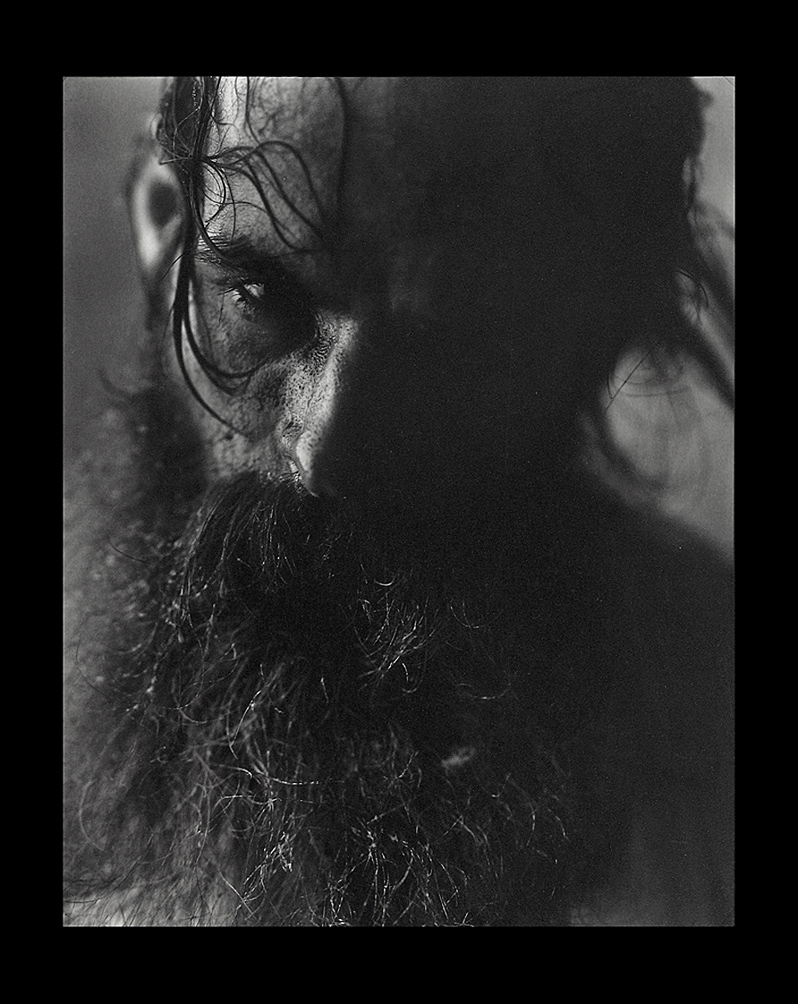

Bratrstvo [Brotherhood] formed by former students of the Brno Secondary School of Applied Arts, the interests of the Bratrstvo art collective (Brotherhood, 1989-1994) span a broad range. But it particularly excelled in photography, music, and literature—fields its members had never formally studied. Not that anyone was able to question that at their time, as in the spirit of preserving conspiracy and inspired by artisanal workshops and brotherhoods, notably the British Pre-Raphaelites, its members Aleš Čuma, Martin Findeis, Petr Krejzek, Roman Muselík, Zdeněk Sokol, and the brothers Pavel, Ondřej, and Václav Jirásek, operated solely under a collective signature. Václav Jirásek, a leading figure in the photography section and a stylist and image-maker for the group’s musical subset “Bratrstvo,” exemplifies the fusion of the music and photography disciplines.

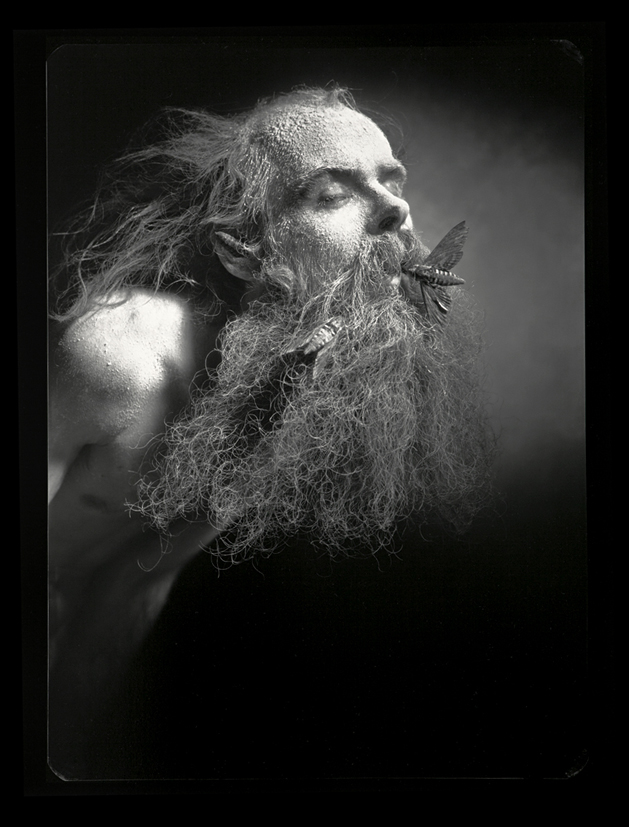

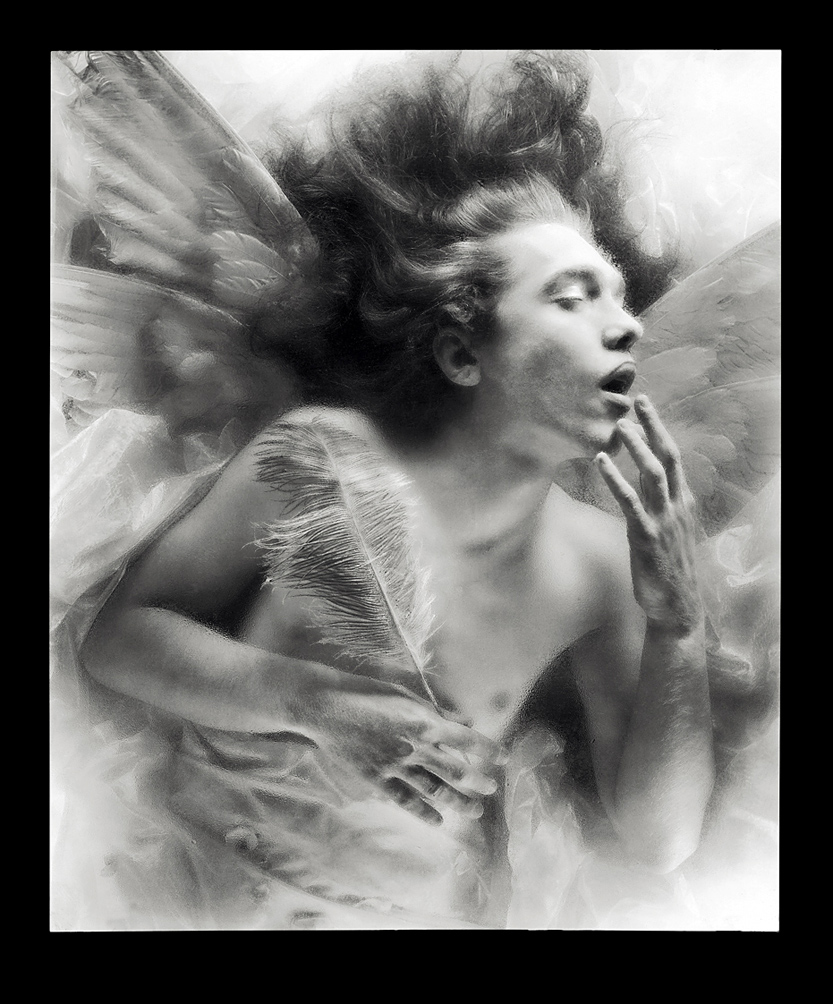

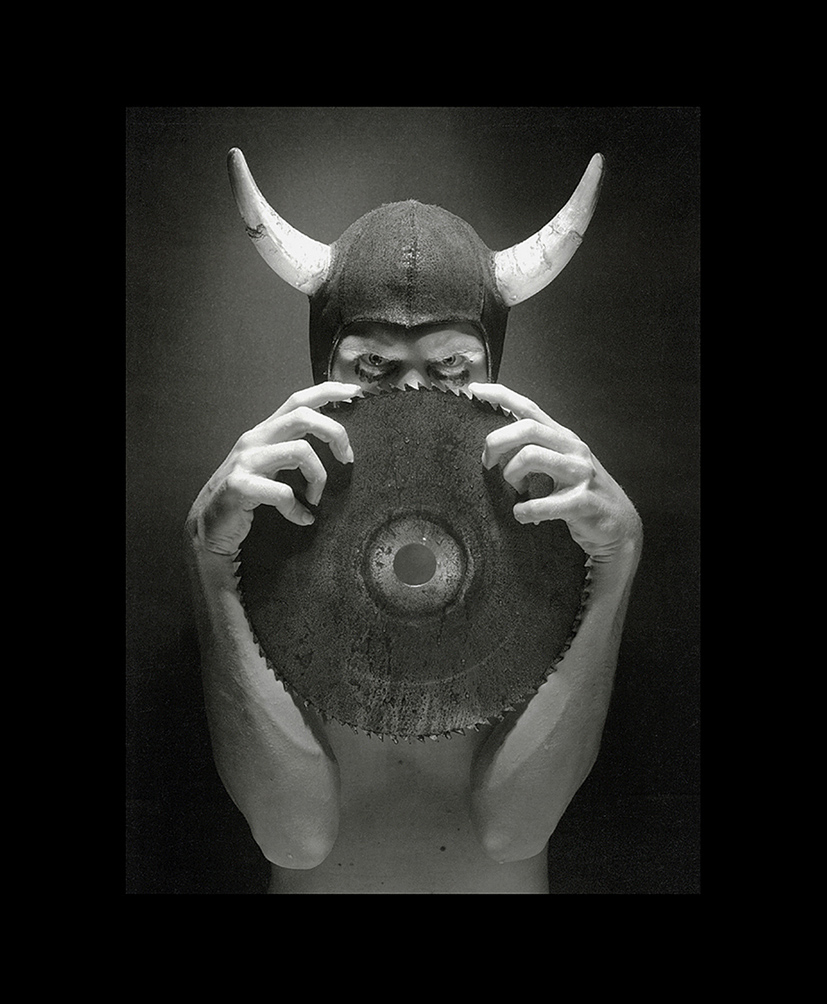

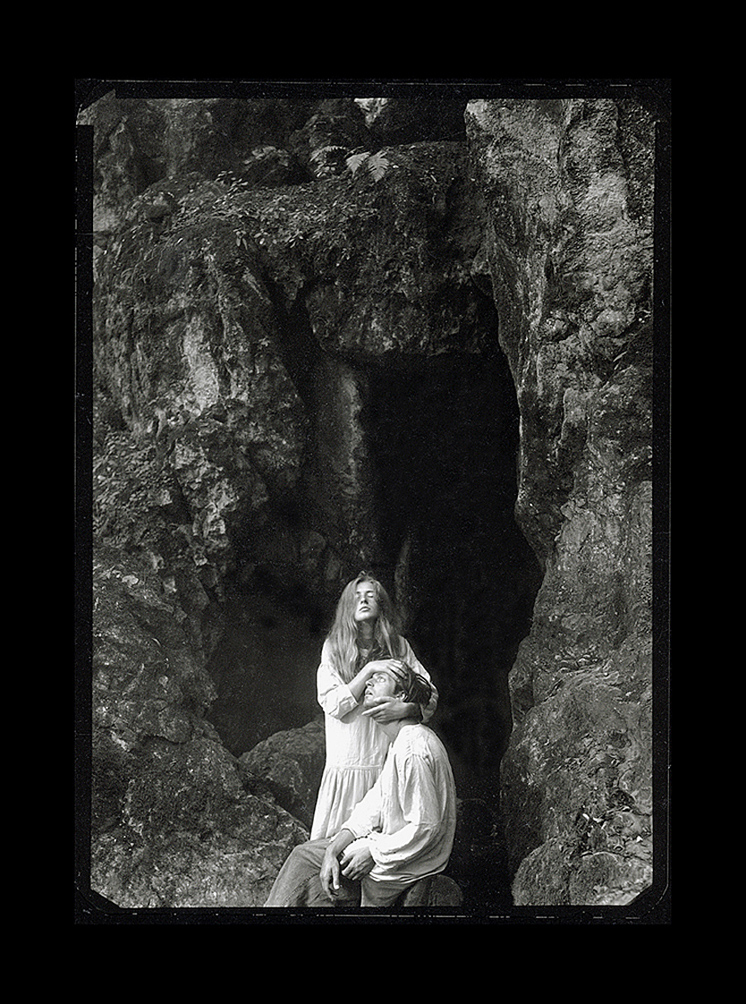

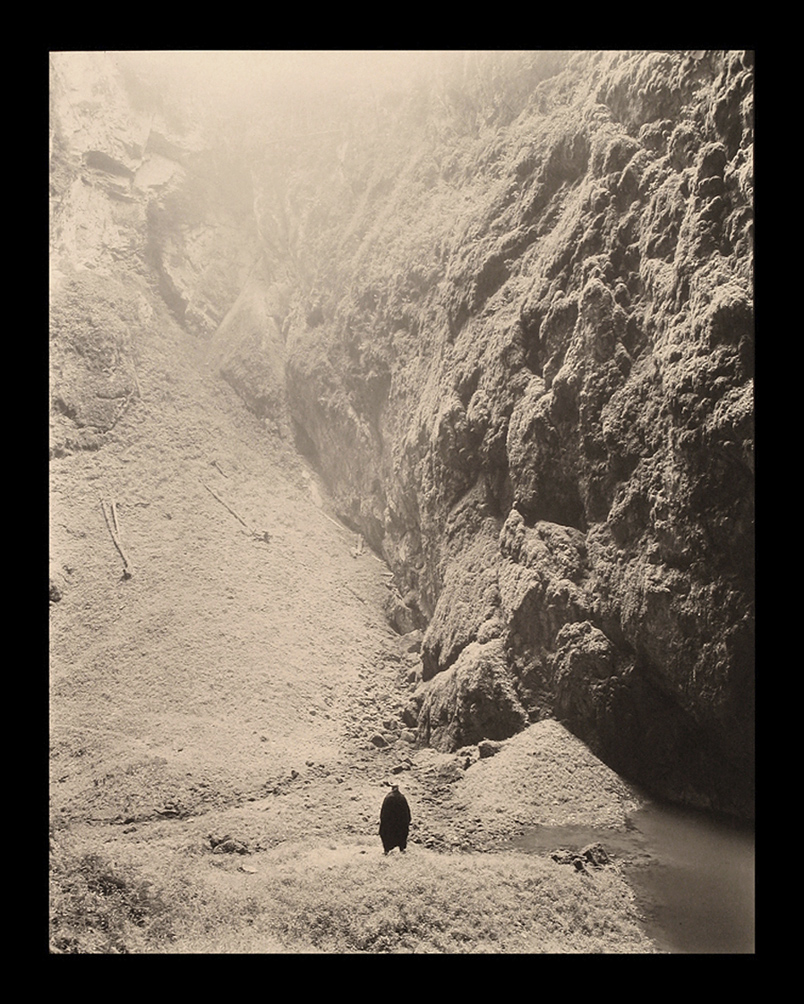

The Bratrstvo’s photographic output recycles intense attributes from various visual forms, encompassing both fine and applied arts—folk ceremonies, old art and Catholicism, totalitarian ideologies, or the iconography of capitalist advertising in fashion or music—without regard for their original purposes or clear new aims. The Bratrstvo members associate their affinity for kitsch and sentimentality, seeking sensitivity, lyricism, naivety, and nostalgia, with their Slavic heritage and Moravian roots. Constructivism, socialist realism, mysticism, national-conservative imagery, and other propagandistic elements appear in their works, akin to peer Central European groups blending Slavic and Germanic influences (e.g., NSK/Laibach). However, the Bratrstvo’s intent is fundamentally different: they requisition these images purely for aesthetic purposes, for their ability to evoke emotions like melancholy and bittersweetness, searching for “intoxicating beauty,” or “intense experience,” irrespective of the source or any apparent political goal.

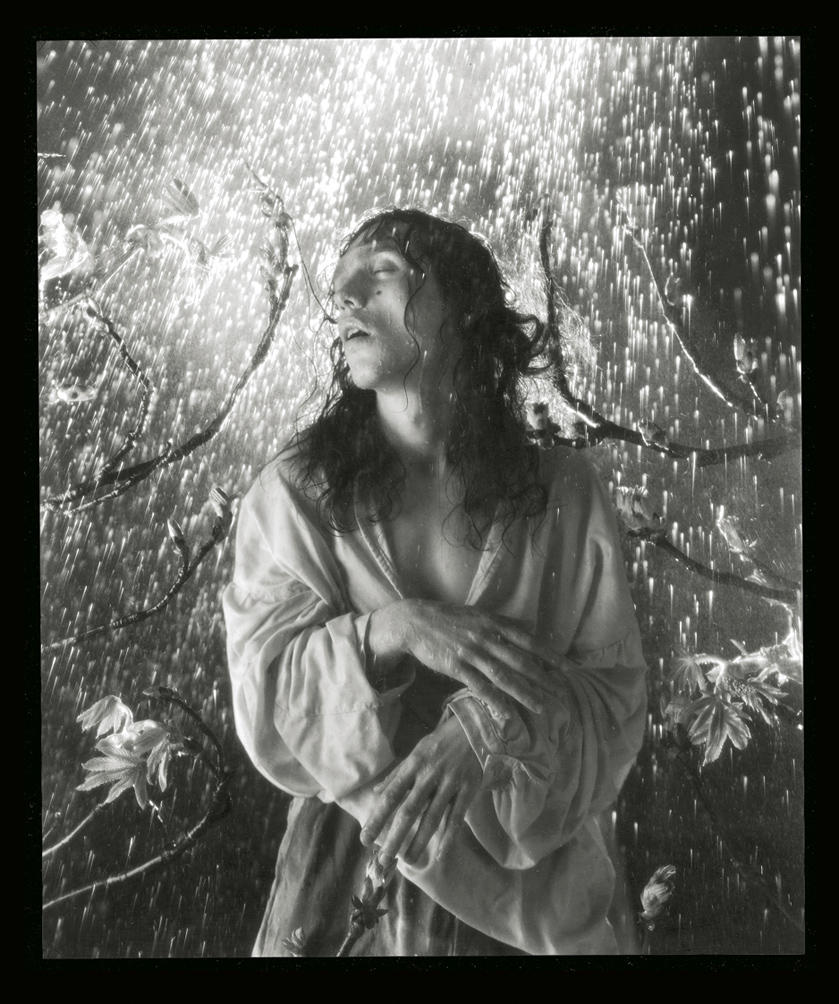

Later Bratrstvo photographs, especially those by Jirásek, who continues to explore the legacy of the collective in his solo work, further harvest and recreate the elements of emotional manipulation and archetypal symbols or “myths” in the broadest sense—late Gothic, Rudolphine mannerism, Rococo, fin de siècle moods of decadence, symbolism, Nietzschean überhumanism and death cults, British New Romantics and generally 20th-century persuasive communication. Again, their goal is not to analyse or demystify their features but primarily to bask in them. When dealing with the sugar-coating of ideological marketing, they focus on the sugar, enjoying their chocolate Santa after Christmas. Though often considered a travesty by viewers, what they are confronted with is mostly a sincere dress-up, reenacting, role-playing, and homage to form. “[Bratrstvo] managed to capture the faint charm of totalitarianism, its pleasure, femininity, homosexuality, and the eroticism of vanished ideologies, leaving only the ‘dead body of paradise,’ ‘a charming drowned,’ as Gogol might say,” writes Výtvarné umění magazine in 1991, referencing John Everett Millais’ Ophelia.

Bratrstvo’s attention to archaic forms that have lost their original purpose, but not their emotional charge, is amplified by the consistent appearance of photographs as artifacts. None of the Brotherhood members were formally trained as photographers, yet technical prowess is an integral part of their effect. They deliberately work with vintage large-format cameras following the tradition of the 19th and early 20th centuries, when photography was an instrumentally demanding craft. Contacts from large negatives are accentuated by the passe-partouts, hand-painted with shellac or decorated with gold leaf, and originally manipulated antique frames. Each showing is “a small pantheon, a shrine, and a cathedral of the spirit, where all components are immensely significant, and everything is subordinated to the construction of the whole. […] We have a fetishist relationship with craftsmanship, creating a new arts & crafts aesthetic. Working with large-format has something ritualistic for us, requiring maximum concentration. Here, pressing the shutter is not accidental or casual, but the result of long-term preparation. Working with a large-format camera is for us a parallel and contemporary counterpart to Gothic panel painting.”

Typical of the intentionally indeterminate, ambiguous nature of Bratrstvo’s work, which caused considerable controversy at the time, was the spontaneous appropriation of two of Jirásek’s photographs of “communist” pathos by the opposition movement for posters during the Velvet Revolution of 1989, adorning, among others, the statue of St. Wenceslas in front of Prague’s National Museum.

Michal Nanoru