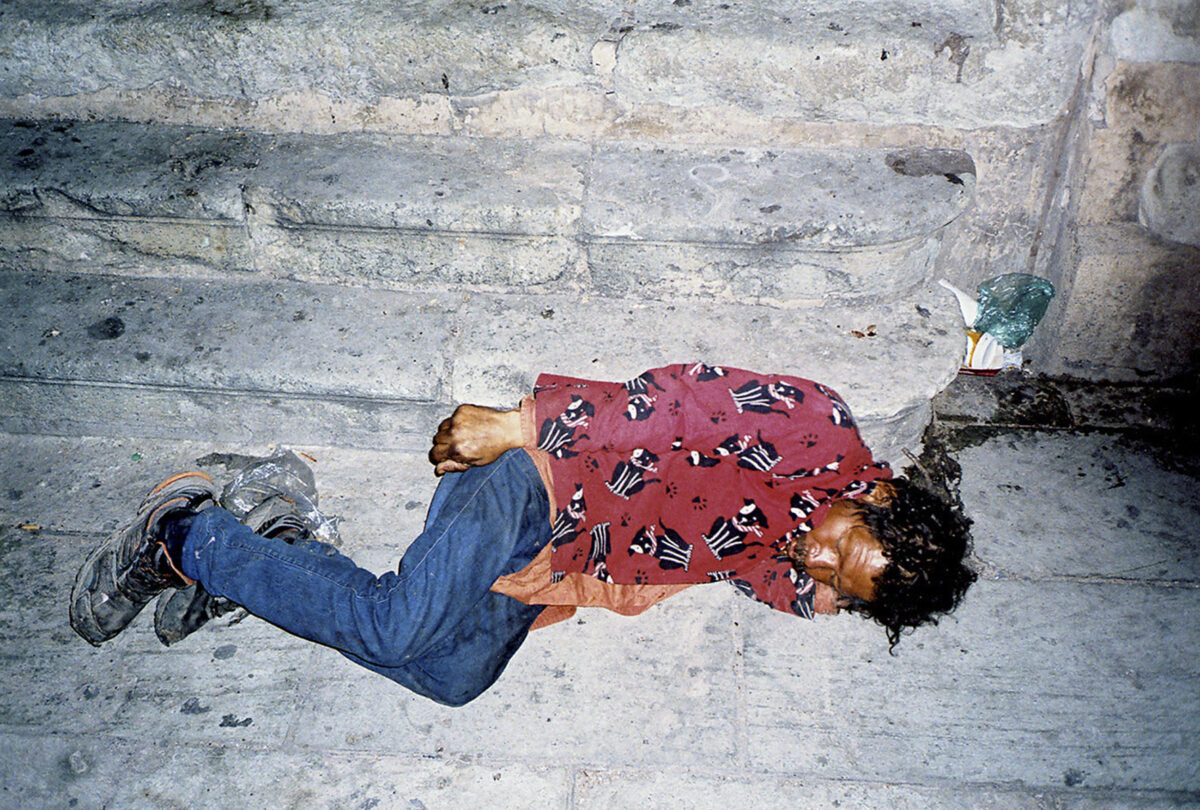

Sleepers

The only thing bad about sleep, so I’ve heard, is that it resembles death, for a sleeping and a dead man are not all that different.

Miguel de Cervantes y Saavedra, The ingenious Gentleman don Quixote of la Mancha

The sleepers, outcasts of society, mostly without success or home, belong to the living dead. For them, gesture remains essential—fundamentally spiritual. The form of a cocoon turned inward, intimacy forced into the public eye—these are the human equivalents of unfinished houses, decaying cars, and forsaken animals.

The sleepers. Even more than their lifeless counterparts, they touch the viewer as images of saints. One is already on his way to heaven, the other has only paused briefly—wearing a rugby-Bosch helmet and childishly jubilant boots, with a staff resting alongside his body—before returning to battle windmills. The charred skeleton of one of their temporary shelters merely affirms the destruction of a life’s project. Like most things in Ironym Kool’s world—norms, order, matter—it crumbles in no man’s land, solitary, isolated, forgotten by God.