Industria

Elaborate review of the state of heavy industry, one of the hallmark visions of modern history, following the significant political and economic shifts of the 1990s

Originally emblematic of engineering and social progress in the 19th and 20th centuries, and later becoming a cornerstone of the Soviet era’s construction of a new workers‘ society from the 1950s through the 1970s, the heavy industry stood at the brink of folding as the millennium turned. The complex, multifaceted project shot between 2004 and 2005 with 4×5 inches large-format analog camera, documents the many interiors of Czech and Moravian metallurgical operations in all their collapsing monumentality and abandonment, but also presents portraits of the remaining factory workers and humanizing, intimate still lifes of their immediate surroundings and homely designs—resounding the ideological package associated with modern ‘temples of labor’, ranging from 19th-century romanticism to echoes of the new objectivity, the Düsseldorf School of Photography, but most pronouncedly Josef Sudek’s ‘St. Vitus Cathedral’.

While the main part of the project forms the almost archaeological documentation of the silenced architectural structures, Jirásek tends to approach the factories as living organisms. First, he follows the interweaving of old buildings with new, and the penetration of industry into the landscape and, subsequently, the return of nature after industrial activity ceases. New pipes and wires sprout on top of old and disused ones resembling the lianas of the jungle, making it clear to him that technology is only a peculiar form of nature. As another fond counterpoint to the mathematically perfect, albeit worn-down, structures, serves the exploration of makeshift and modified furniture pieces and still lifes of the ingenious efforts to domesticate the industrial and often noxious environments into intimate retreats. Both utilitarian and decorative “installations” of recycled cheap materials and DIY chairs, tables, or ashtrays are presented with all the dignity of original design creations and testaments of the “irrepressible desire to make the inhospitable working environment inhabitable”, often resemblant of a life in the apocalyptic future of our universe.

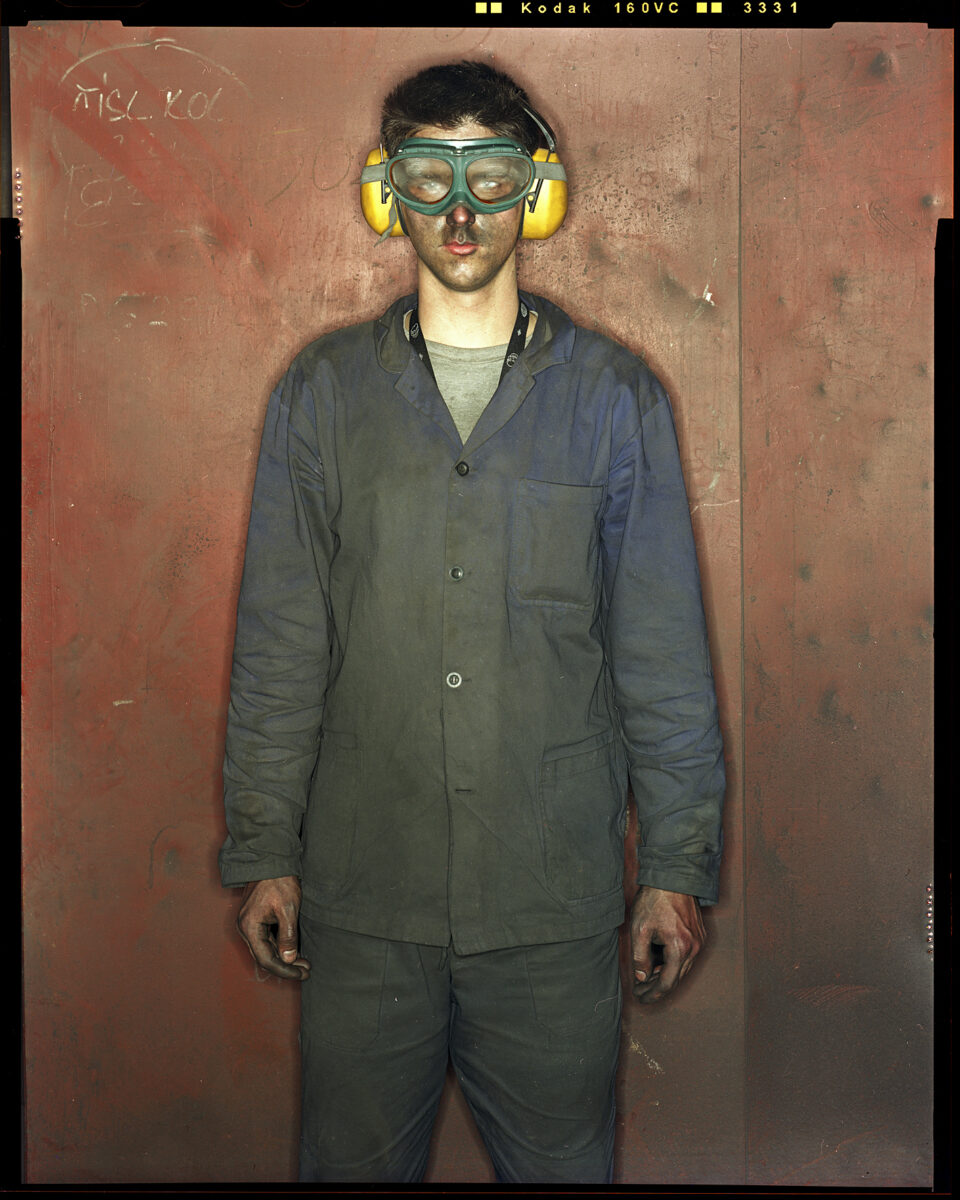

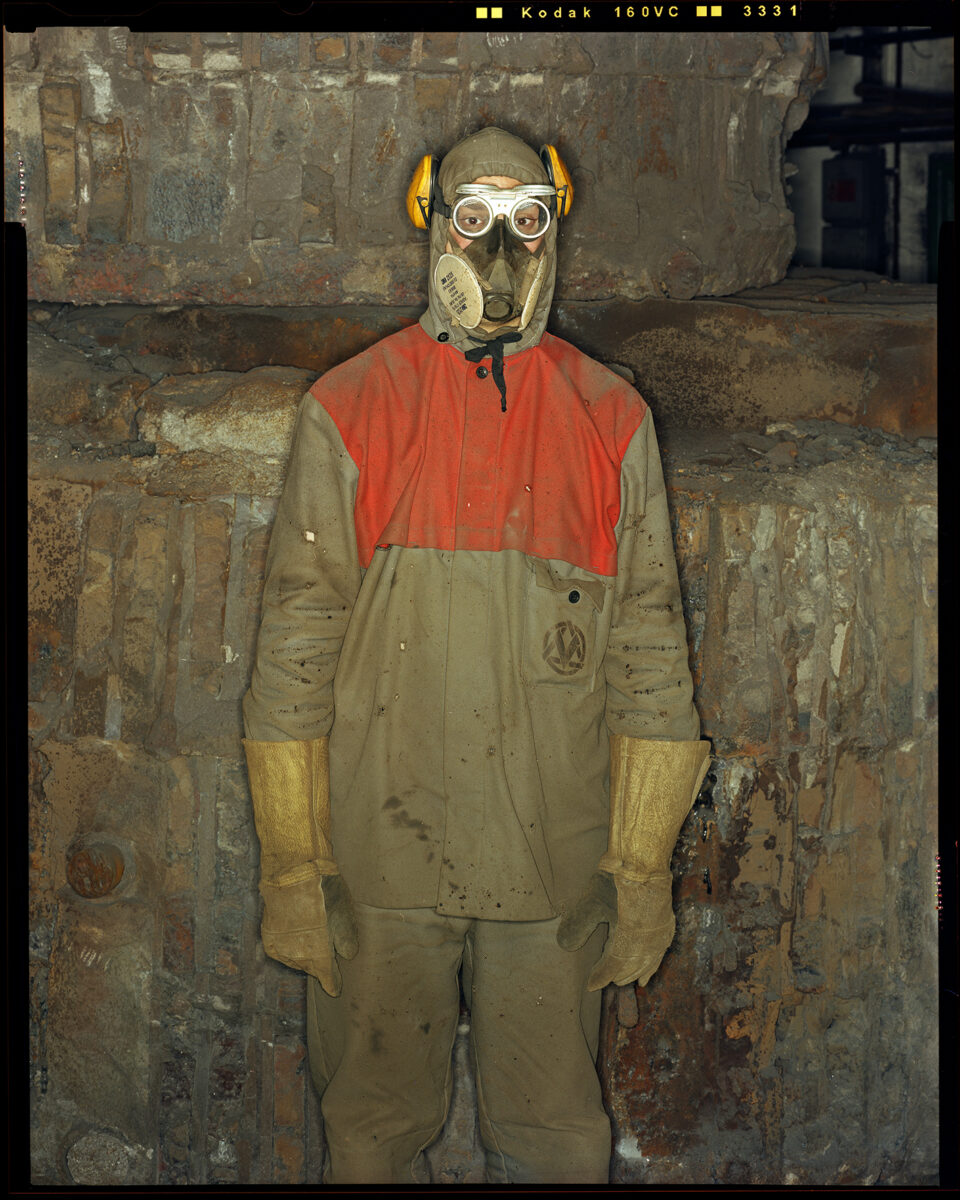

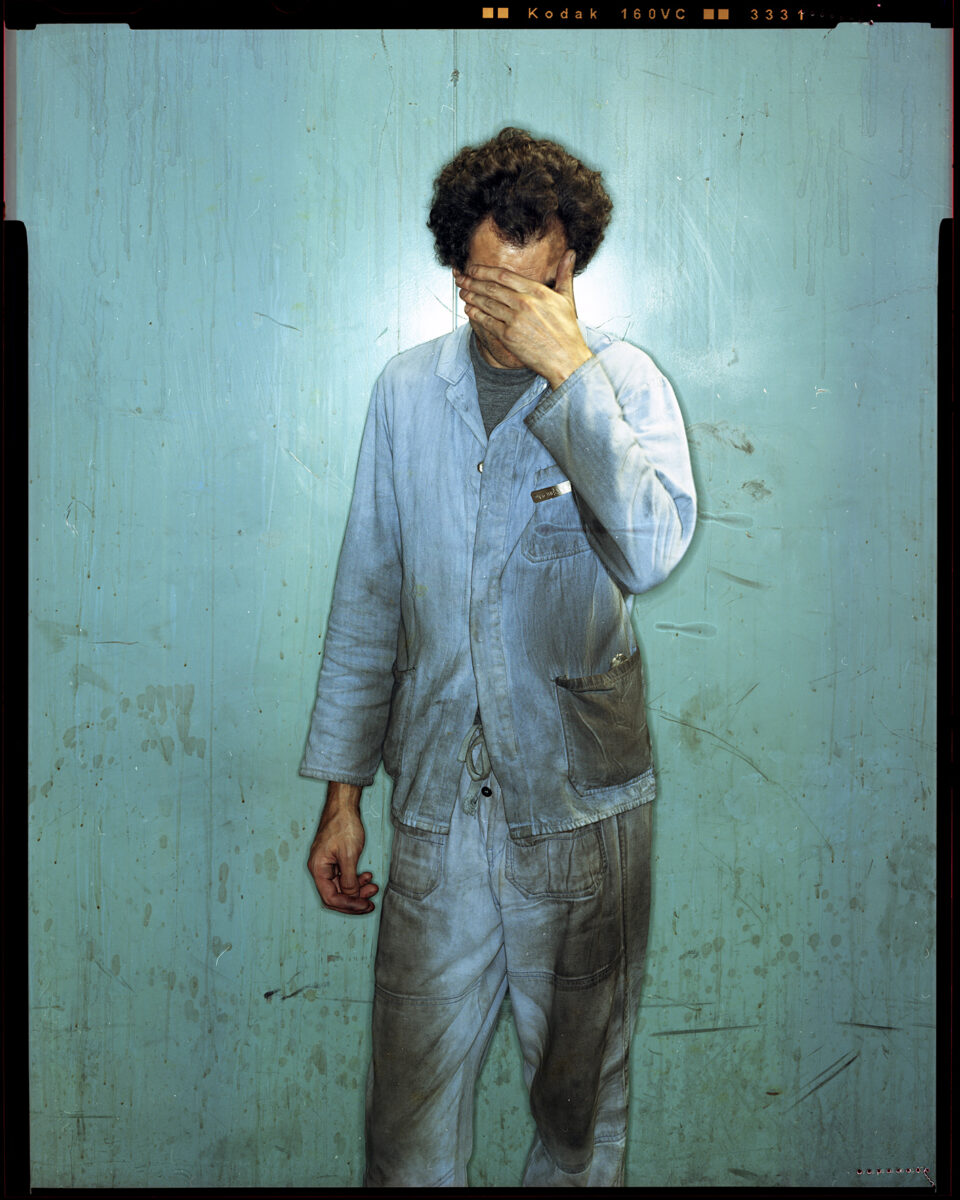

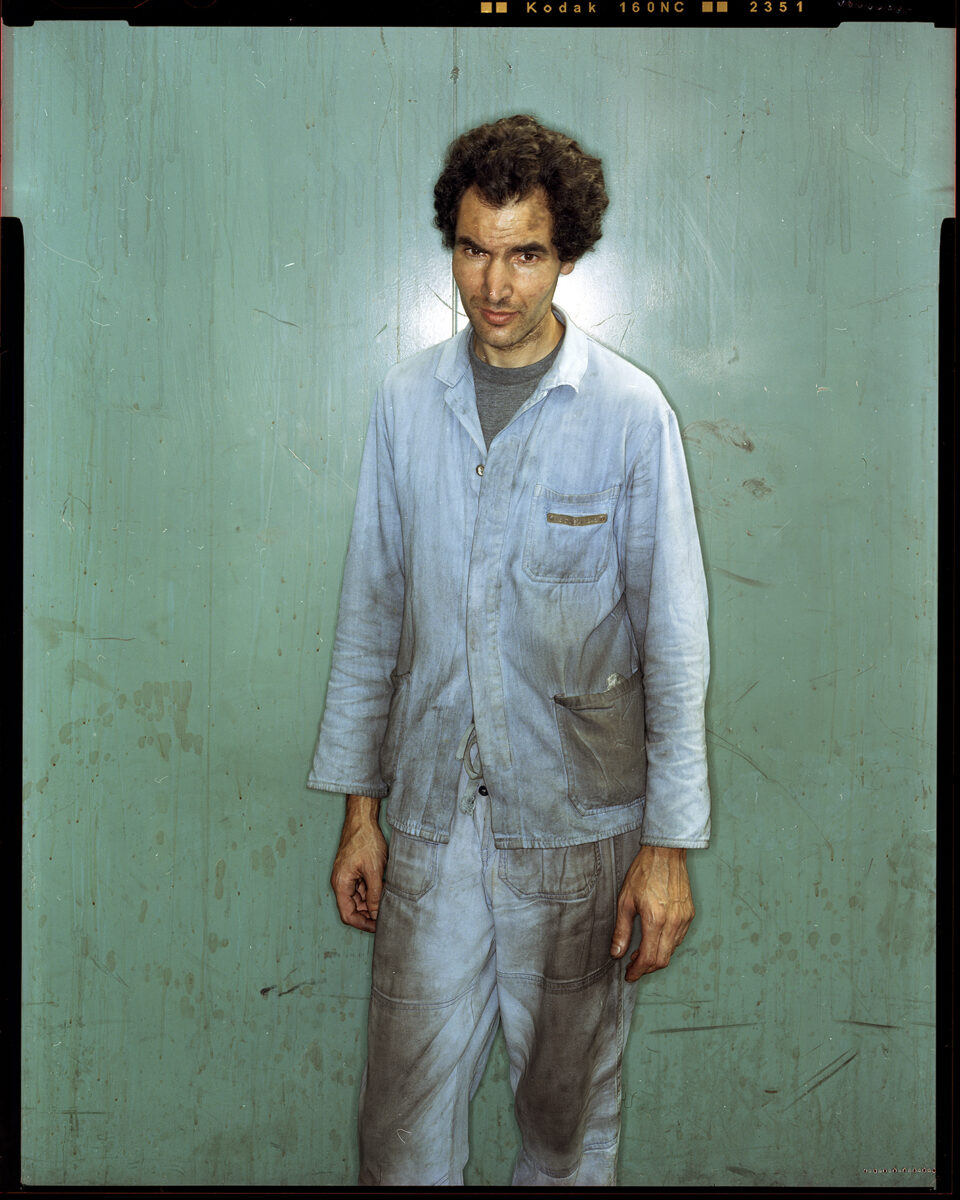

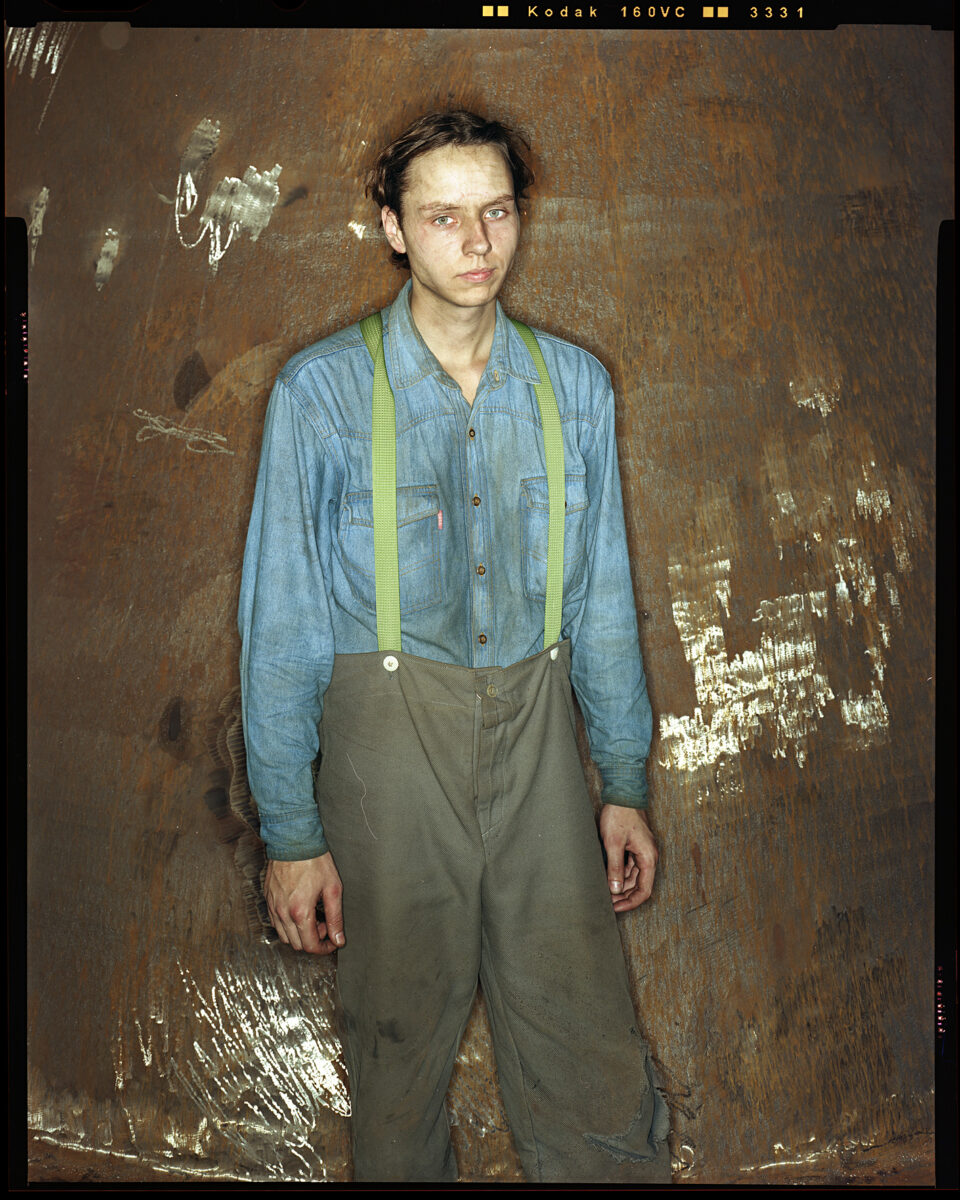

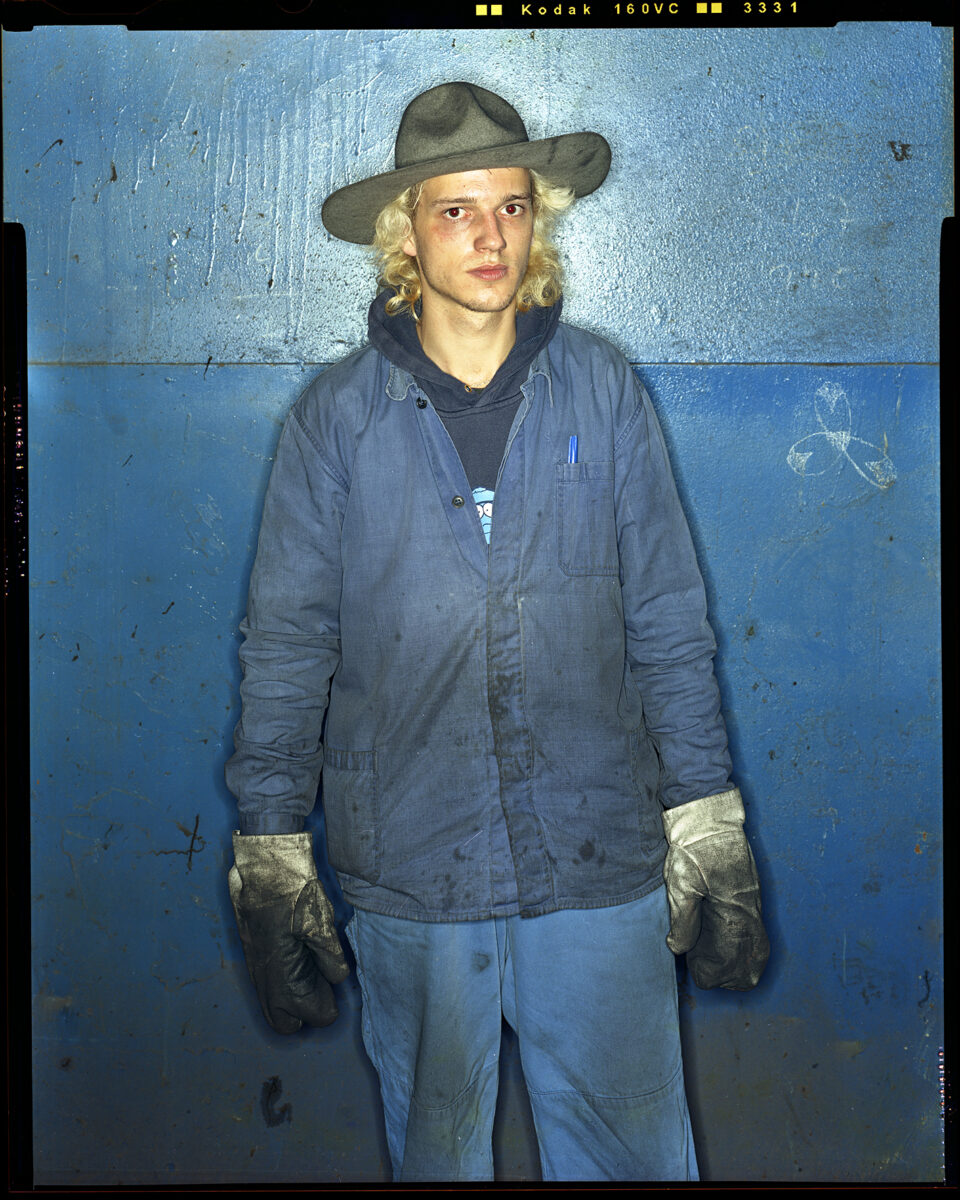

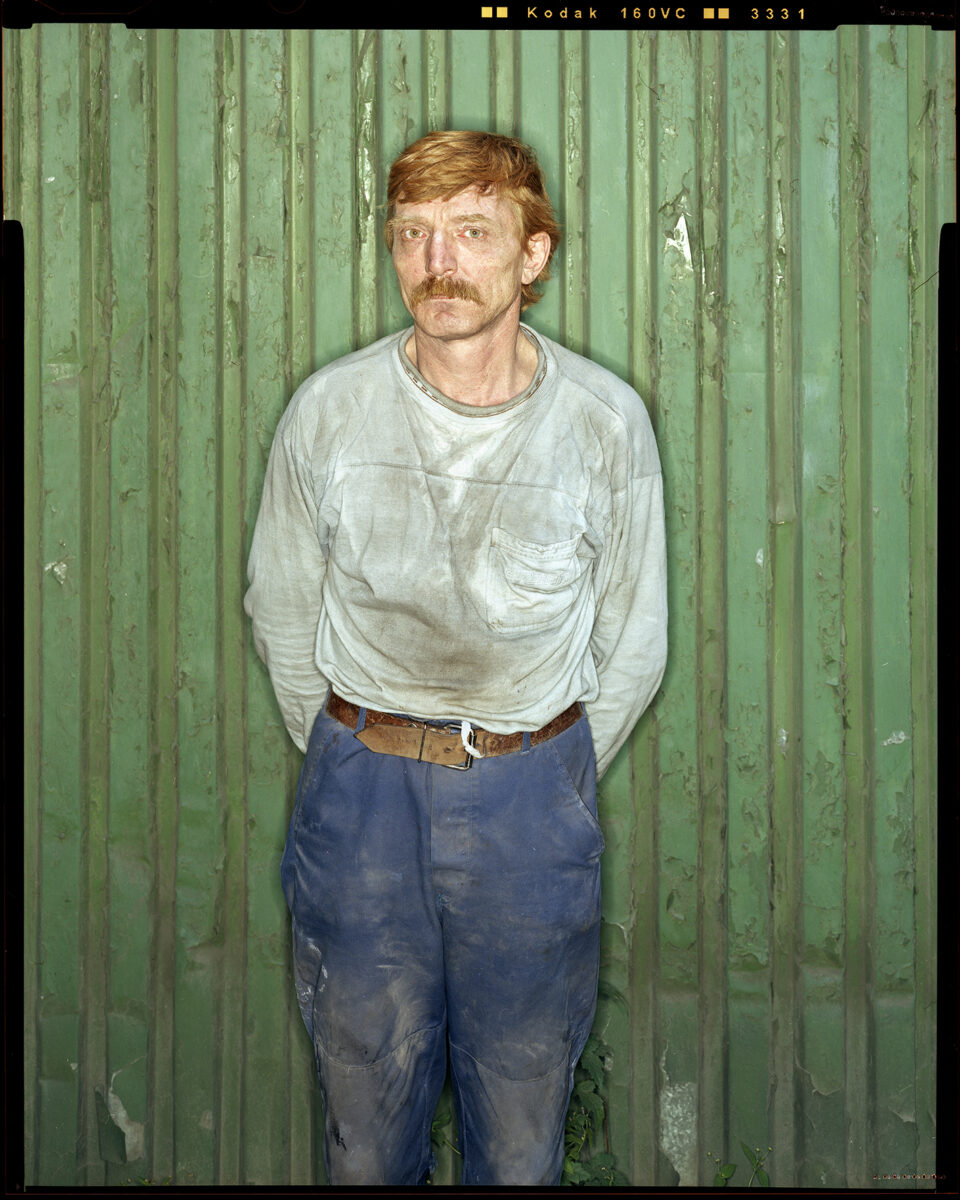

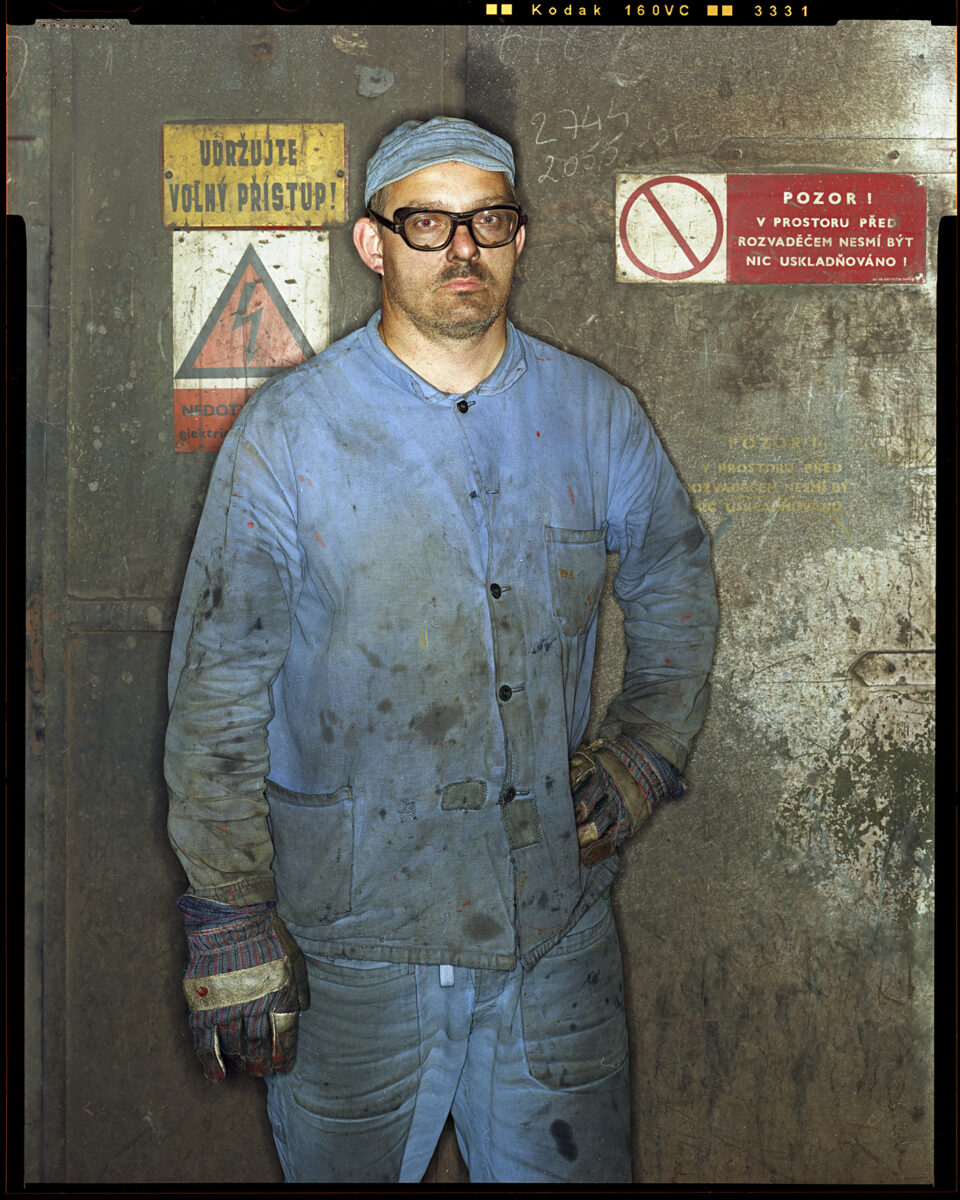

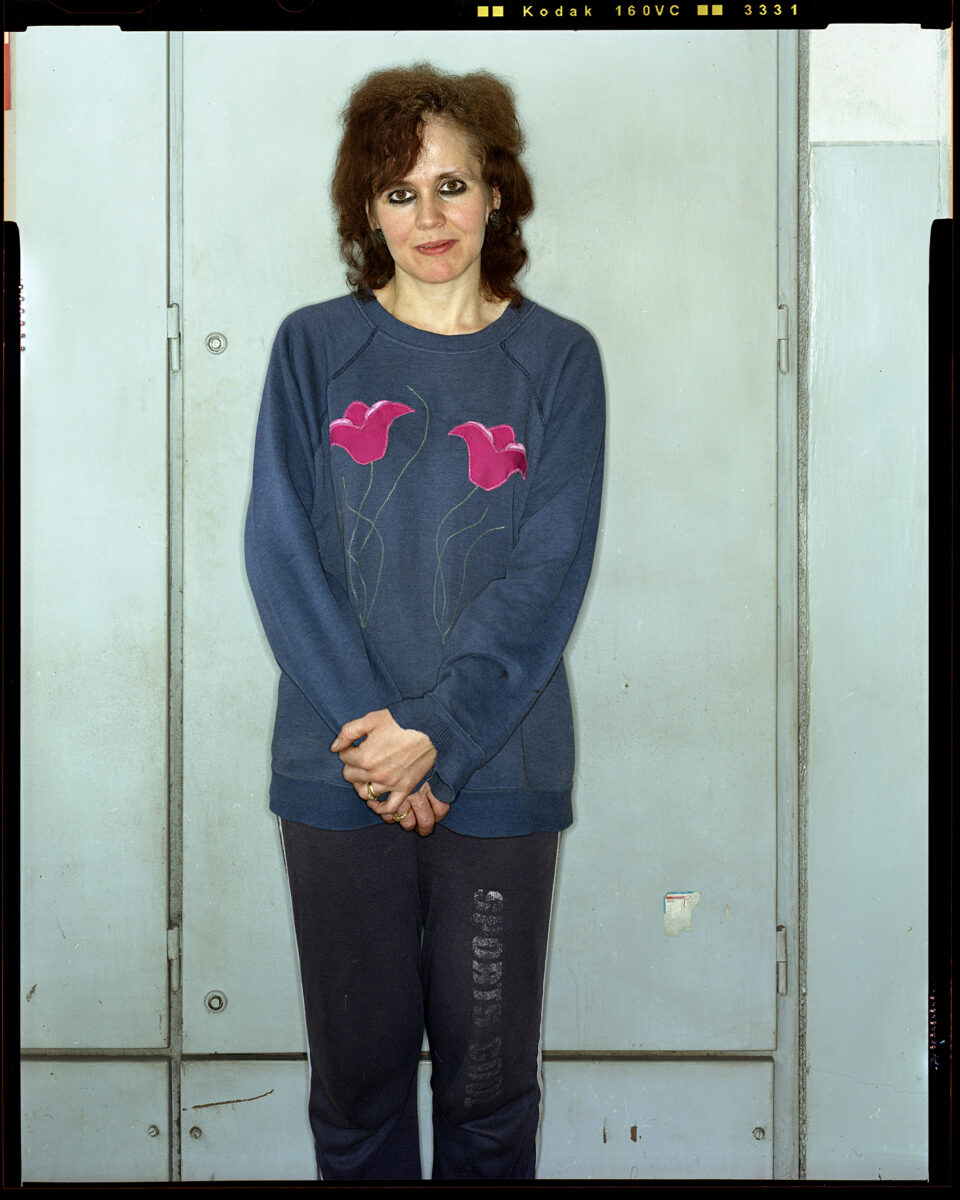

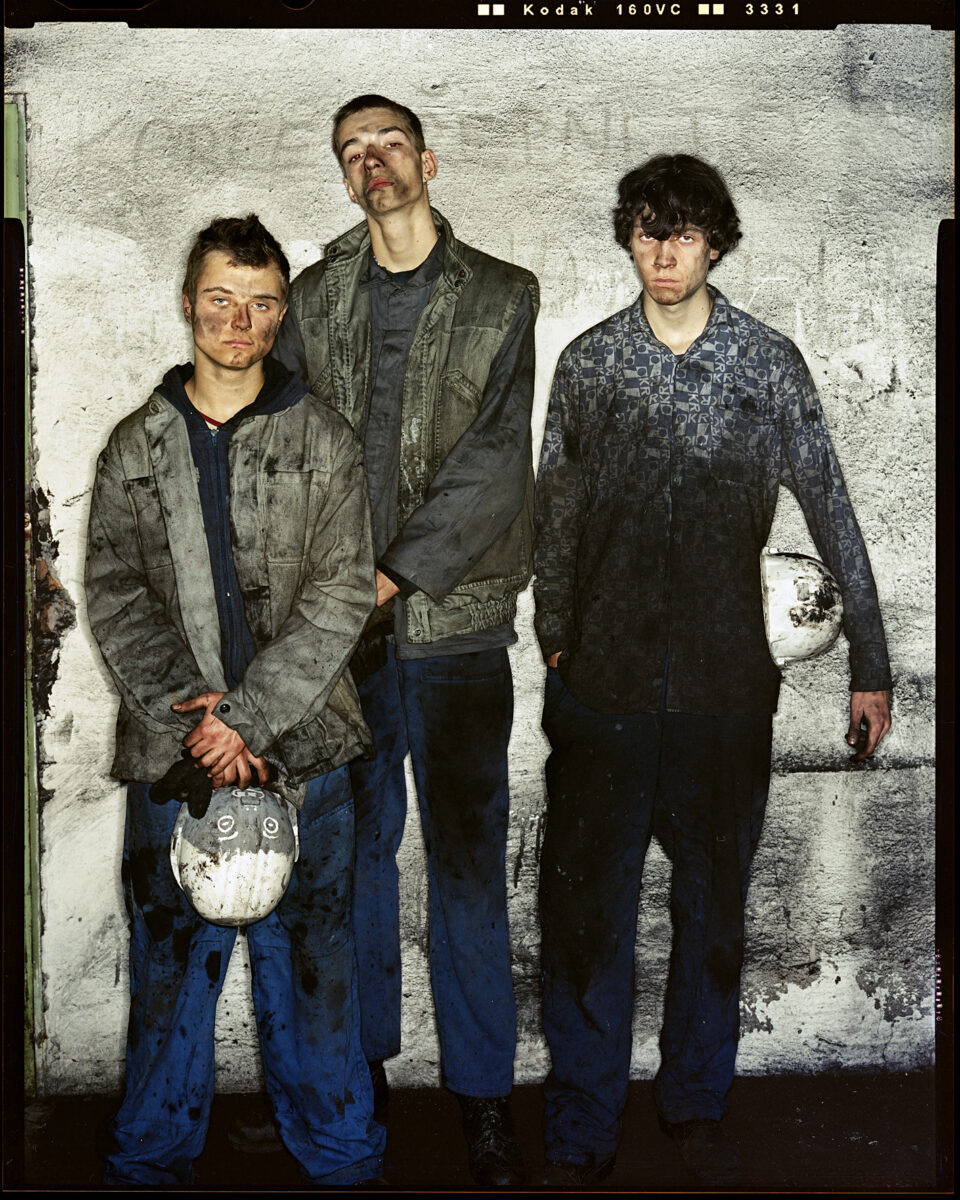

In the second part of the project, the actual forgotten workers come to the fore in civil and objective, mostly half-length portraits. Either life-sized or larger than life, they stand grounded in the subject’s gesture and veristic detail that bear as much of traces of tar as of August Sander and gothic and renaissance masters. The scruffy personalities tested by harsh realities extend the sense of downfall, yet unquestionably also distinctive beauty and pride. Jirásek’s “heroes” are photographed in close proximity to where he met them, with the background often echoing the subjects in color or structure, as if the protagonists have become a part or product of their working environment. Just as with their improvised designs, their tattered overalls are given a treatment of couture objects and their protective gear handling of a bearer of mystery or heroic attribute.

Metallurgical processes have always contained something mystic, akin to an inferno – yet the dream of heavy industry’s epochal significance has swiftly vanished, leaving behind only the colossal halls of rust-bound machinery, and amid heaps of dust and slag, a metaphor for Europe’s long-lost dream of the titanic deployment of universal engineering as a guarantee of prosperity and high living standards. In its scenes of the decay and desolation of the overblown ideas of the past, ‘Industria’ depicts the end of the Industrial Revolution, or, the idea that the future would never end.